When you hear "power generation," your mind might leap to colossal wind farms or towering nuclear plants. But beneath the surface, driving a significant portion of the world's electricity, are the often-unsung heroes: turbine generators. These intricate machines convert raw energy from various sources—be it rushing water, superheated steam, or expanding hot gases—into the mechanical work that spins a generator, ultimately producing electricity. Understanding the Types & Classification of Turbine Generators isn't just for engineers; it's key to appreciating the ingenuity behind our power grid, how different environments are harnessed, and where future energy innovation might take us.

Choosing the right turbine generator for a specific application is a nuanced decision, influenced by everything from the available energy source to environmental conditions and desired output. It's a complex dance between physics, engineering, and economics, ensuring we extract the maximum possible power efficiently and reliably.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways on Turbine Generators

- Core Function: Turbine generators convert fluid energy (water, steam, gas) into mechanical rotation, then into electrical power.

- Hydro Turbines Lead Classification: Hydraulic turbines are primarily classified by energy at the inlet (Impulse or Reaction), flow direction (Tangential, Radial, Axial, Mixed), available head (High, Medium, Low), and specific speed.

- Impulse vs. Reaction: Impulse turbines (e.g., Pelton) use purely kinetic energy at the inlet, while Reaction turbines (e.g., Francis, Kaplan) utilize both kinetic and pressure energy.

- Major Hydro Types: Pelton for very high heads, Francis for medium heads, and Kaplan for low heads and high flow rates.

- Beyond Hydro: Steam Turbine Generators (for thermal power plants) and Gas Turbine Generators (for natural gas or jet fuel) are also critical components of the global energy mix.

- Crucial Selection Factors: Head, flow rate, specific speed, rotational speed, efficiency, cavitation risk, and operational flexibility dictate the ideal turbine choice.

- Optimizing Performance: Factors like governing systems, draft tubes, and careful cavitation management are vital for efficiency and longevity.

The Heart of Hydro: How Water Powers Our World

Let's begin with one of the oldest and most elegant forms of power generation: hydroelectricity. Here, hydraulic turbines are the workhorses, converting the potential and kinetic energy of water into the rotational motion that fuels electric generators. Imagine a powerful river, dammed and channeled, its force precisely directed to spin massive blades. That's the magic of a hydro turbine.

This conversion happens as water strikes the turbine's blades, transferring its energy and causing the rotor to spin. The design of these blades and the turbine's overall structure are meticulously engineered to maximize this energy transfer, adapting to various water conditions.

Decoding Hydro Turbine Classifications

Understanding how hydraulic turbines are categorized provides a roadmap to their function and application. Engineers look at several key parameters to classify these machines, helping them select the perfect fit for a given site.

1. Energy at the Inlet: Impulse vs. Reaction

The fundamental difference lies in how the turbine extracts energy from the water.

- Impulse Turbines: These rely purely on the kinetic energy of water. Think of a high-pressure jet of water striking a series of buckets or blades. The pressure at both the inlet and outlet of an impulse turbine is typically atmospheric. The water hits the runner, changes direction, and leaves at a lower velocity, having transferred its momentum.

- Reaction Turbines: These turbines utilize both the kinetic energy and the pressure energy of the water. As water flows through a reaction turbine, it undergoes a significant pressure drop across the runner blades. The rotor forces are generated by accelerating the water flow and by this pressure differential. Unlike impulse turbines, reaction turbines are fully submerged in water, and the pressure changes as water passes through them.

2. Flow Direction Through the Runner

How water moves through the spinning part of the turbine (the runner) is another key differentiator:

- Tangential Flow: Water strikes the runner blades tangentially, meaning it approaches along the edge, like a paddle wheel.

- Radial Flow: Water flows either inward or outward, perpendicular to the axis of rotation, impacting blades that radiate from the center.

- Axial Flow: Water flows parallel to the axis of rotation, moving directly through the runner.

- Mixed Flow: A hybrid design where water enters radially and exits axially, combining characteristics of both.

3. Head at Inlet: High, Medium, or Low

The "head" refers to the vertical drop height of the water, which dictates the potential energy available.

- High Head: Typically, sites with significant elevation drops (hundreds of meters).

- Medium Head: Moderate elevation drops (tens to a couple of hundred meters).

- Low Head: Relatively small elevation drops (a few meters to a few tens of meters).

4. Specific Speed: Tailoring to Conditions

Specific speed is a crucial dimensionless parameter that helps characterize a turbine's design for a particular head and flow rate. It essentially indicates the speed at which a geometrically similar turbine would run under a unit head (1 meter) to produce unit power (1 kilowatt).

- Low Specific Speed: Suited for high heads and low flow rates.

- Medium Specific Speed: Ideal for medium heads and medium flow rates.

- High Specific Speed: Best for low heads and high flow rates.

This metric is vital for selecting the most efficient turbine type for specific site conditions, helping engineers find the sweet spot between rotational speed, output, and cost.

Diving Deeper: Specific Types of Hydro Turbines

With the classification framework in mind, let's explore the most common types of hydraulic turbines you'll encounter.

Impulse Turbines: Harnessing the Jet

As we discussed, impulse turbines rely on the kinetic energy of a high-velocity water jet. They are typically chosen for high-head, low-flow applications where water is scarce but powerful.

Pelton Turbine

Invented by Lester Ella Pelton in the 1870s, the Pelton turbine is perhaps the most recognizable impulse turbine.

- How it Works: A nozzle converts the high-pressure water into a high-speed jet, which then strikes a series of specially shaped buckets mounted on the runner. The buckets are designed to split the jet in two and deflect it almost 180 degrees, maximizing the momentum transfer. The turbine operates at atmospheric pressure at both the inlet and outlet.

- Applications: Ideal for very high heads (often above 350 meters) and relatively low flow rates. Think mountainous regions with steep waterfalls.

- Key Characteristics: Purely kinetic energy at inlet, tangential flow, low specific speed (8.5-43).

- Governing: Speed regulation is achieved by controlling the water flow using a "spear" (needle valve) within the nozzle or a "deflector" that diverts the jet away from the buckets.

Cross-Flow Turbine

Developed by Anthony Michel in 1903, the Cross-flow turbine offers a unique design.

- How it Works: Water passes through the cylindrical runner twice—first from the outside in, then from the inside out—before exiting. This double pass helps increase efficiency, especially at part loads.

- Applications: Suited for low to medium heads (10–70 meters) and high flow rates. It's often used in small hydro applications due to its robust design and ability to handle silt-laden water.

- Key Characteristics: Low-speed machine, good efficiency over a wide range of flow rates.

Reaction Turbines: Pressure and Motion Combined

Reaction turbines are distinct because they extract energy from both the pressure and velocity of the water. The turbine's runner is fully submerged in a pressurized flow, and the design creates a pressure drop across the blades as the water moves through, generating force.

Francis Turbine

Invented by James B. Francis, the Francis turbine is a versatile workhorse of hydroelectric power.

- How it Works: Water enters the runner radially and exits axially, making it a mixed-flow turbine. It extracts energy from high-pressure fluid. The runner blades are carefully shaped to create a pressure differential as water flows over them, driving the rotation. A key component, the "draft tube," connected to the turbine's outlet, helps recover pressure and safely discharge water to the tailrace.

- Applications: Dominant for medium heads (45-400 meters) and medium to high discharges (10-700 m³/s). It's one of the most common hydro turbine types globally.

- Key Characteristics: Mixed flow, medium specific speed (50-340), extracts both kinetic and pressure energy.

Kaplan Turbine

Developed by Viktor Kaplan in 1913, the Kaplan turbine is renowned for its adaptability.

- How it Works: It features adjustable blades, similar to a ship's propeller, allowing it to maintain high efficiency across a wide range of flow rates and heads. Water flows axially through the runner.

- Applications: Primarily used for low heads (typically 10-70 meters, but can go lower) and very high discharges (4-55 m³/s). Ideal for run-of-river plants or sites with fluctuating water levels.

- Key Characteristics: Axial flow, high specific speed (255-860), adjustable blades for optimal performance, extracts both kinetic and pressure energy.

- Part Load Operation: Kaplan turbines are particularly useful for low heads with part loads due to their adjustable blades, offering better efficiency than fixed-blade propeller turbines in such conditions.

Hydraulic Turbine Classification Summary

For quick reference, here's how the main hydraulic turbine types stack up against the classification criteria:

| Classification Factor | Pelton Turbine | Francis Turbine | Kaplan Turbine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy at Inlet | Impulse (Kinetic) | Reaction (Kinetic & Pressure) | Reaction (Kinetic & Pressure) |

| Flow Direction | Tangential | Mixed (Radial-Axial) | Axial |

| Head (Application) | Very High Heads (>350m) | Medium Heads (60-150m) | Low Heads (<60m) |

| Specific Speed | Low (8.5-43) | Medium (50-340) | High (255-860) |

The Science of Efficiency: Making Turbines Work Better

Beyond simply knowing the types, understanding how turbines operate and how their performance is measured is crucial for maximizing power generation.

Governing: Keeping the Lights On (and Stable)

A steady electricity supply requires stable frequency, which means a stable generator speed. This is where governing comes in. A governor system automatically regulates the water flow through the turbine to maintain a constant rotational speed, even as the electrical load changes.

For impulse turbines, this might involve moving a spear to adjust the nozzle opening or using a deflector to temporarily divert water away from the buckets. Reaction turbines typically use adjustable "wicket gates" at the runner inlet to control flow.

Measuring Performance: The Efficiencies

Engineers use various efficiency metrics to gauge how well a turbine converts available energy into useful power:

- Hydraulic Efficiency (η_h): How effectively the turbine converts the water's energy into mechanical energy delivered to the runner blades.

Power Delivered to Runner / Power Supplied at Inlet- Mechanical Efficiency (η_m): How much of the mechanical power delivered to the runner is actually transferred to the turbine shaft, accounting for friction and other mechanical losses.

Power at Shaft / Power Delivered to Runner- Overall Efficiency (η_o): The comprehensive measure of how much of the initial water energy is converted into useful power at the turbine shaft.

Power at Shaft / Power Supplied at Inlet- Note: Overall Efficiency = Hydraulic Efficiency × Mechanical Efficiency

Unit Quantities: Standardizing Performance

To compare different turbines or predict a turbine's performance under varying conditions, engineers use "unit quantities":

- Unit Speed (N_u): The speed of the turbine if it were operating under a 1m head.

- Unit Power (P_u): The power generated by the turbine if it were operating under a 1m head.

- Unit Discharge (Q_u): The discharge (flow rate) through the turbine if it were operating under a 1m head.

These normalized values allow for standardized performance prediction, regardless of the actual head or flow rate at a given site.

The Draft Tube: A Crucial Component for Reaction Turbines

Reaction turbines rely heavily on a component called the draft tube. This is a gradually widening (divergent) tube connected to the turbine outlet, extending below the tailrace (the water level downstream).

Its primary functions are twofold:

- Pressure Recovery: By slowing down the water as it exits the turbine, the draft tube helps recover some of the kinetic energy as pressure energy. This increases the pressure at the turbine outlet, often above atmospheric pressure, which helps maximize the useful head available to the turbine.

- Safe Discharge: It efficiently discharges the "spent" water from the turbine into the tailrace with minimal energy loss and turbulence.

Without a draft tube, much of the head and thus potential power from a reaction turbine would be wasted.

The Menace of Cavitation

While efficiency is key, reliability is paramount. One of the most significant operational challenges for reaction turbines, especially those operating under high heads, is cavitation.

- What it is: Cavitation occurs when the static pressure of the liquid (water, in this case) falls below its vapor pressure. This causes the liquid to "boil" locally, forming vapor pockets or bubbles. When these bubbles are carried into regions of higher pressure, they rapidly collapse, creating intense shockwaves.

- Why it's a problem: These implosions can erode turbine blades and surfaces, create noise and vibration, and significantly reduce efficiency and lifespan. It's like tiny hammers relentlessly pounding on the metal.

- Causes: High dynamic pressure near fast-moving blades or, more commonly, at the turbine exit (where pressure is naturally lower, especially if the turbine is set high above the tailrace) can lead to a drop in static pressure below the water's vapor pressure.

- Avoidance:

- Design: Maintain static pressure above the liquid's vapor pressure at all points of flow, particularly at the draft tube inlet.

- Operating Parameters: Control pressure head, flow rate, and exit pressure within safe limits.

- Placement: Lowering the turbine's physical setting relative to the tailrace can help increase pressure at the outlet.

- Materials: Using cavitation-resistant materials for critical components.

- Model Tests: Extensive model testing helps determine cavitation-free operating parameters before full-scale construction.

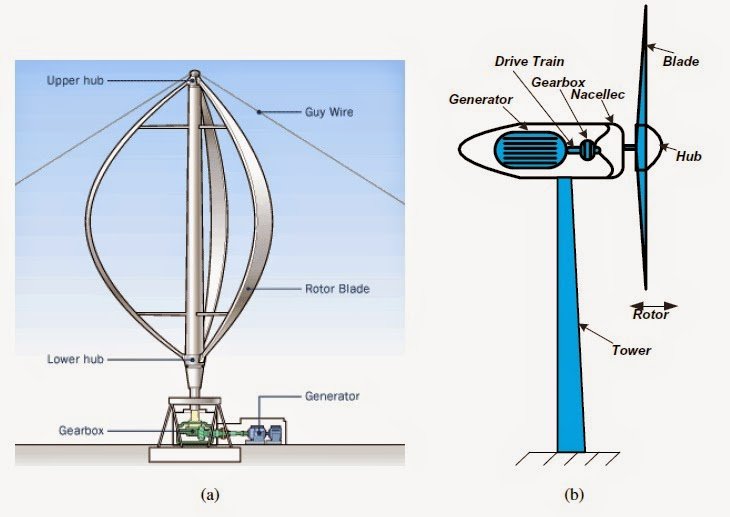

Beyond Hydro: The Broader World of Turbine Generators

While hydraulic turbines are fascinating and crucial, the term "turbine generator" encompasses a much wider array of technologies. At its core, a turbine generator system integrates a prime mover (the turbine), an alternator (the electric generator), along with auxiliaries, protection systems, and controls. This integrated unit is designed to convert fluid energy into mechanical work, and then into usable electricity.

Let's look at the other major players in the turbine generator landscape.

Steam Turbine Generators: Powering Thermal Plants

Steam turbine generators are the backbone of most large-scale thermal power plants, whether they burn coal, natural gas, biomass, or use nuclear energy.

- How they Work: High-pressure, high-temperature steam expands through a series of bladed stages within the turbine. This expansion drives the rotation of the turbine shaft, which in turn spins the connected electrical generator. A condenser typically creates a vacuum at the turbine exhaust, maximizing the pressure differential and thus the energy extracted from the steam. Gland sealing systems prevent steam leakage and air ingress.

- Applications: Utility-scale electricity generation, industrial process plants (especially for cogeneration).

- Efficiency Drivers: Optimized blade profiles, advanced sealing technologies, and precise control systems are continuously upgraded to improve "heat rate" (the amount of heat energy required to produce one unit of electricity) and reliability. In cogeneration, backpressure steam turbines are used to produce both electricity and process steam for industrial applications.

Gas Turbine Generators: The Workhorses of Modern Power

Gas turbine generators have become increasingly popular for their quick start times, lower emissions compared to coal, and high efficiency in combined cycle applications.

- How they Work: Air is drawn into a compressor, pressurized, and then mixed with fuel (typically natural gas or diesel) in a combustion chamber. The ignited fuel-air mixture produces high-temperature, high-pressure gases that expand through a turbine section, driving both the compressor and the electrical generator.

- Applications: Peaking power plants, base-load power (especially in combined cycle), industrial power generation, aviation.

- Efficiency Drivers: High firing temperatures, advanced compressor pressure ratios, sophisticated inlet air conditioning, and meticulous hot section maintenance are critical for performance. The real efficiency gains come in combined cycle plants, where the hot exhaust gases from the gas turbine are used to generate steam in a heat recovery steam generator (HRSG) to drive a secondary steam turbine generator, dramatically increasing overall net efficiency.

Choosing the Right Turbine Generator: A Strategic Decision

Selecting the optimal turbine generator system is a complex engineering and economic challenge. It requires a holistic view of the project, taking into account site-specific conditions, operational demands, and long-term costs.

Here are the critical factors influencing turbine generator selection:

- Available Head (for Hydro) / Fuel Source & Steam Conditions (for Thermal):

- Hydro: As seen, this directly dictates turbine type: Pelton for >350m, Francis for 60-150m, Kaplan for <60m.

- Thermal: The type of fuel (coal, gas, biomass), availability, and the desired steam pressure and temperature conditions determine steam turbine design or gas turbine fuel choice.

- Specific Speed: For hydro, high specific speed is paramount for low head/large output projects. It ensures the turbine can operate at a rotational speed compatible with the generator without becoming prohibitively large or costly.

- Rotational Speed: The turbine's rotational speed must precisely match the synchronous speed of the coupled electrical generator to produce power at the grid's required frequency (e.g., 50 Hz or 60 Hz). Gearboxes can adjust speeds, but direct drive is often preferred for large units.

- Efficiency: Always a top priority. Selecting a turbine with the highest overall efficiency across its expected operating range directly impacts profitability and resource utilization. Modern designs focus on maintaining high efficiency even at part loads.

- Part Load Operation: How efficiently does the turbine operate when it's not at its maximum output?

- Kaplan turbines excel here for low-head hydro due to adjustable blades.

- Deriaz turbines are also used for variable hydro loads.

- For thermal plants, turndown ratios and efficiency curves at varying loads are crucial.

- Cavitation (for Hydro): Especially critical for reaction turbines. Thorough analysis of cavitation indices and careful design are necessary to prevent damage and ensure safe, long-term operation. This also influences how high the turbine can be placed above the tailrace.

- Shaft Orientation: Large reaction turbines typically use vertical shafts due to space and hydraulic considerations. Large impulse turbines often prefer horizontal shafts.

- Water Quality (for Hydro): More critical for reaction turbines where impurities (silt, sand) can cause rapid wear, especially under high head conditions. Pelton turbines can be more tolerant but still suffer from abrasion.

- Duty Cycle & Grid Requirements: Is the plant for base load, peaking, or grid support? This impacts startup times, ramp rates, and operational flexibility requirements. Hydro turbines are excellent for peaking and grid support due to their rapid response.

- Ambient Conditions & Water Limitations: Environmental factors like air temperature, humidity, and cooling water availability (for thermal plants) play a significant role in overall plant design and efficiency.

- Maintenance Strategy & Lifecycle Costs: Ease of maintenance, spare parts availability, and projected lifespan are vital economic considerations.

Properly sizing auxiliaries (e.g., cooling systems, lubrication), excitation systems (for the generator's magnetic field), and protection systems (for fault detection) ensures the entire turbine generator system performs at its rated capacity reliably and safely. For a more comprehensive overview of these complex systems, you might find our Comprehensive turbine generator guide helpful.

Actionable Insights for Enhanced Efficiency and Reliability

Whether you're operating a hydro, steam, or gas turbine generator, continuous improvement is the name of the game. Here are key areas to focus on:

- Master the Thermodynamics (for Thermal Turbines): Maximize the expansion ratio of your working fluid. For steam turbines, this means optimizing steam conditions (pressure, temperature), maintaining excellent condenser performance, and tuning control schedules to minimize losses during expansion.

- Refine Aerodynamics and Hydraulics: For all turbine types, reducing flow losses is paramount. This involves using advanced blade profiles, maintaining tight tip clearances (the gap between rotating and stationary parts), and ensuring smooth, clean surface finishes to minimize friction and turbulence.

- Embrace Heat Rate Discipline: For thermal plants, rigorously manage operational factors like fouling (build-up on heat exchange surfaces), leakage (steam, gas, water), proper alignment, and parasitic loads (energy consumed by auxiliary equipment). Regular, quantified performance testing helps identify and rectify deviations.

- Leverage Digital Monitoring and Analytics: Implement advanced sensor technology for vibration, temperature, pressure, and performance analytics. Utilizing this data enables condition-based maintenance, allowing you to predict and address potential issues before they lead to costly unplanned outages. Predictive maintenance saves significant time and money compared to reactive repairs.

Powering Forward: Your Role in the Energy Landscape

Understanding the Types & Classification of Turbine Generators isn't just an academic exercise; it's a window into the foundational technology that powers our modern world. From the serene, majestic power of a hydro dam to the roaring precision of a gas turbine, these machines are at the heart of our energy infrastructure.

As technology evolves and the demand for sustainable, reliable power grows, the innovation in turbine design and operation continues. Whether you're an engineer designing the next generation of power plants, an operator striving for peak efficiency, or simply an engaged citizen interested in how electricity reaches your home, appreciating these intricate systems empowers you to make informed decisions and contribute to a more energy-conscious future. The journey of energy conversion, from raw source to electrified grid, starts with the turbine, and mastering its complexities is mastering the future of power.